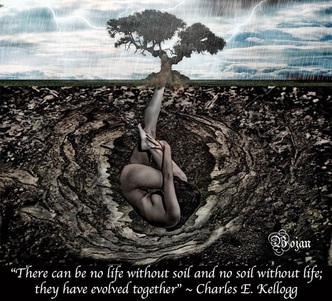

| Ever since I started farming three years ago, I have become more and more fascinated, amazed and enthralled by that which most people take great care to avoid: fungus, bacteria, slugs, spiders, worms and all the amazing life found in healthy soils. My husband has a new nickname for me, “The Soil Evangelist”. It seems wherever I go, some way or another, the conversation ends up with me talking about soil and especially the importance that microbes play in the soil and in our lives. My husband and I recently gave a service at our Unitarian Universalist Fellowship on “Culturing a Reverence for Food”, which of course I thought required a bit of expounding on the virtues of soil, as all life begins in the soil. I'm happy to say that the sermon was well received, and so here, I present some of what I said about soil and microbes. |

I recently read a great book called Cows Heal the Planet, by Judith Schwartz. In it, Schwartz describes how we can look to soil as a crucible for many of our current social, economic and environmental crises: desertification, biodiversity loss, water security, climate change and extreme weather events, cleaning up toxins in our environment. We are understanding more and more the critical role that microbialy rich soil plays in our general health and wellbeing, and problems such as obesity, malnutrition, violence, hunger, poverty and economic stability. At their core, these problems are all manifestations of the long-term and widespread mistreatment of our soils.

The good news is that even though these issues seem deep, intractable and overwhelming at times, there is so much hope, as soil restoration practices are healing the Earth. Thus, our food choices- the way we grow, purchase, prepare and eat our food has the ability to heal or hurt ourselves, our community and our Earth.

The good news is that even though these issues seem deep, intractable and overwhelming at times, there is so much hope, as soil restoration practices are healing the Earth. Thus, our food choices- the way we grow, purchase, prepare and eat our food has the ability to heal or hurt ourselves, our community and our Earth.

Soil life

Soil life Consider biodiversity, which starts in the soil. Indeed, the diversity above ground is a reflection of the diversity in the soil. There are presumed to be 10 million species of soil bacteria, and three million species of soil fungi. Unfortunately, typical commodity cropland (of which there are 349 million acres in the lower 48 U.S.A.) has about 5,000 species and we need at least 25,000 for plants and ecosystems to function anywhere near their potential.

Another 45 million acres in the U.S.A. are lawns, which are also either low or devoid of soil microorganism diversity. You may be surprised that, from a soil microorganism's point of view, a suburban lawn is akin to an agricultural monoculture. Whether it is Kentucky blue grass or soy beans, one type of plant doesn’t support the wide array of soil microbiology needed for healthy soils.

It takes hundreds of years to build soil using geological processes of weathering rock, but soil can be built rather quickly by biological processes: microbes, plants and animals all working together to fulfill their respective roles in the ecosystem. The practice of holistic planned grazing, championed by Allan Savory, where large groups of livestock are rotated through different pastures in order to mimic natural herding behavior to protect against predators so that a disturbance is created and then the land is allowed to regenerate, is remaking deserts into productive lands again, supporting and feeding people and sequestering carbon in the soil. Soil that’s rich in carbon holds water like a sponge, buffering against droughts and floods and refilling aquifers.

Carbon also lends fertility to the soil and sustains plant and microbial life. Unfortunately, most agriculture in the U.S.A. today is soil depleting rather than soil building. Microbes are hampered by widely used chemical fertilizers purported to yield bumper crops. Chemical fertilizers have the effect of depleting soil compounds that they don’t contain, including soil organic carbon and trace minerals. Additionally, in the past 150 years, between 50 and 80% of organic carbon in the topsoil has gone airborne due to poor agricultural practices of overgrazing livestock and leaving soil bare after it has been harvested.

Without microbes, we wouldn't have oxygen to breathe. Photosynthetic microbes are responsible for about half of the photosynthesis on Earth, simultaneously increasing the amount of oxygen and decreasing the amount of carbon dioxide in the air. Through this process, microbes are helping to mitigate some of the greenhouse gasses that cause global warming. Some soil scientists have concluded that if we improve 50% of the world’s agricultural land, we could sequester enough carbon in the soil to bring atmospheric CO2 back to preindustrial levels in five years.

Another 45 million acres in the U.S.A. are lawns, which are also either low or devoid of soil microorganism diversity. You may be surprised that, from a soil microorganism's point of view, a suburban lawn is akin to an agricultural monoculture. Whether it is Kentucky blue grass or soy beans, one type of plant doesn’t support the wide array of soil microbiology needed for healthy soils.

It takes hundreds of years to build soil using geological processes of weathering rock, but soil can be built rather quickly by biological processes: microbes, plants and animals all working together to fulfill their respective roles in the ecosystem. The practice of holistic planned grazing, championed by Allan Savory, where large groups of livestock are rotated through different pastures in order to mimic natural herding behavior to protect against predators so that a disturbance is created and then the land is allowed to regenerate, is remaking deserts into productive lands again, supporting and feeding people and sequestering carbon in the soil. Soil that’s rich in carbon holds water like a sponge, buffering against droughts and floods and refilling aquifers.

Carbon also lends fertility to the soil and sustains plant and microbial life. Unfortunately, most agriculture in the U.S.A. today is soil depleting rather than soil building. Microbes are hampered by widely used chemical fertilizers purported to yield bumper crops. Chemical fertilizers have the effect of depleting soil compounds that they don’t contain, including soil organic carbon and trace minerals. Additionally, in the past 150 years, between 50 and 80% of organic carbon in the topsoil has gone airborne due to poor agricultural practices of overgrazing livestock and leaving soil bare after it has been harvested.

Without microbes, we wouldn't have oxygen to breathe. Photosynthetic microbes are responsible for about half of the photosynthesis on Earth, simultaneously increasing the amount of oxygen and decreasing the amount of carbon dioxide in the air. Through this process, microbes are helping to mitigate some of the greenhouse gasses that cause global warming. Some soil scientists have concluded that if we improve 50% of the world’s agricultural land, we could sequester enough carbon in the soil to bring atmospheric CO2 back to preindustrial levels in five years.

Culturing mycorrhizae on spelt bran

Culturing mycorrhizae on spelt bran As a Natural Farmer, I spend a lot of time actively culturing mycorrhizae and other soil microbes and spreading them around to my blueberry field and crop beds. Mycorrhizae are "fungus roots" and act as an interface between plants and soil. They grow into the roots of crops and out into the soil, increasing the root system many thousands of times over. They act symbiotically, using enzymes to convert nutrients in the soil into food that plants can use and taking carbohydrates from the plants and turning them into nutrients the soil can use: sequestering carbon in the soil for later use. Miles of fungal filament can be present in an ounce of healthy soil. Mycorrhizal inoculation of soil increases the accumulation of carbon by depositing glomalin, which in turn increases soil structure by binding organic matter to mineral particles in the soil. It is glomalin that gives soil its tilth, its texture and rich feel, its buoyancy and its ability to hold water.

The food we eat is only as good as the soil from which it springs. Microbes living in the soil provide plants with natural protection from pests and diseases, by breaking down minerals and making them available to plants. Plants then, take the minerals and synthesize vitamins and other essential nutrients. If chemical agricultural inputs are used, you don’t get high levels of biological soil activity from bacteria and fungi and the minerals stay "locked up" in the soil, unavailable to plants.

Americans spend the lowest percentage of our income on food of any nation in the history of the world, but what good is producing abundant cheap food when the food is not healthy? We are in a situation where we can buy oranges that are completely devoid of Vitamin C. Across the board, levels of key mineral nutrients- zinc, calcium, manganese, iron, phosphorus, magnesium and copper in our food crops have declined by an average of 50 to more than 100% over the last century. Some scientists believe that today’s high obesity rates are paradoxically, a symptom of malnutrition due to diets deficient in micronutrients.

So, we hear a lot about avoiding bad stuff in our food (chemical residues, GMO’s, antibiotics, etc.), but that is only part of the problem, the other part is the good stuff that is missing. What our bodies need and through our senses seek out are “plant secondary metabolites,” which depend on the presence of trace minerals – released by, microbes! These are tannins and essential oils. That which makes basil smell like basil and leeks smell like leeks. This is why we instinctively recoil when we bite into a huge red strawberry that has absolutely no taste. Our bodies recognize that it also has no nutrition.

Foods devoid or deficient in microbes, grown on soil devoid or deficient in microbes, leads to poor health, physical and emotional. Dr. Natasha Campbell- McBride, MD in her book Gut and Psychology Syndrome has pioneered the use of probiotics, or beneficial microorganisms, in the treatment of children and adults with mental illness and behavioral and learning disabilities (ADHD, autism, etc). Our bodies, much like plants, need a wide variety of beneficial microorganisms in our gut in order to extract and make available to our bodies the minerals and vitamins in the foods that we eat. Much like a pesticide, which indiscriminately kills all insects and microbes on a plant, whether they are beneficial or not, when we bathe in and drink chlorinated water and use antibacterial soap, we indiscriminately kill all microbes in and on our bodies, most of which, we need to be healthy.

So, we hear a lot about avoiding bad stuff in our food (chemical residues, GMO’s, antibiotics, etc.), but that is only part of the problem, the other part is the good stuff that is missing. What our bodies need and through our senses seek out are “plant secondary metabolites,” which depend on the presence of trace minerals – released by, microbes! These are tannins and essential oils. That which makes basil smell like basil and leeks smell like leeks. This is why we instinctively recoil when we bite into a huge red strawberry that has absolutely no taste. Our bodies recognize that it also has no nutrition.

Foods devoid or deficient in microbes, grown on soil devoid or deficient in microbes, leads to poor health, physical and emotional. Dr. Natasha Campbell- McBride, MD in her book Gut and Psychology Syndrome has pioneered the use of probiotics, or beneficial microorganisms, in the treatment of children and adults with mental illness and behavioral and learning disabilities (ADHD, autism, etc). Our bodies, much like plants, need a wide variety of beneficial microorganisms in our gut in order to extract and make available to our bodies the minerals and vitamins in the foods that we eat. Much like a pesticide, which indiscriminately kills all insects and microbes on a plant, whether they are beneficial or not, when we bathe in and drink chlorinated water and use antibacterial soap, we indiscriminately kill all microbes in and on our bodies, most of which, we need to be healthy.

Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin D. Roosevelt Microbes break down plant residue and animal wastes so that they can be recycled into nutrient rich soil amendments. Because of their special adaptations, some microbes actually degrade, rendering harmless, chemicals that are extremely dangerous to humans. These microbes can help clean up gasoline leaks, oil spills, sewage, nuclear waste, heavy metals, and many other types of pollution that our modern society has created. Modern economic theory calls this pollution an "externality" and so, incredibly, our global economic system does not take the environment into account. This disconnect between the economy and the natural world is a fantasy that we continue to believe at our own peril. We need to make the link between our economic and ecological cycles. All new wealth comes from the soil and natural ecological function. When we erode our soil, we erode our ability to create wealth. As Franklin D. Roosevelt once said, "A nation that destroys its soil, destroys itself."

And so, we must consciously choose and seek out foods that are grown with a reverence for life, from microbes in the soil to chickens raised on pasture. We can choose to grow a portion of our own food and lovingly tend to the soil and thus, all that depends on it, and we can also support local, sustainable farmers, shop at farmer’s markets and local food coops, strengthening local economies and community connections.

Each action creates a ripple of love and healing, and we find that not only are we healing the Earth, but our minds, bodies and souls as well. This summer, may the beauty and nourishment of what the Earth is creating underneath your feet at this very moment and what the farmers are giving life to with their hands and hearts, grace you and those you hold dear.

Each action creates a ripple of love and healing, and we find that not only are we healing the Earth, but our minds, bodies and souls as well. This summer, may the beauty and nourishment of what the Earth is creating underneath your feet at this very moment and what the farmers are giving life to with their hands and hearts, grace you and those you hold dear.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed